UPDATE: Contest over! Thanks to everyone for participating. Winners will be notified shortly.

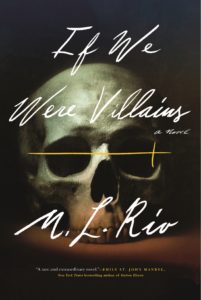

We haven’t done a book giveaway in a long time, so let’s fix that right now with a good one! Introducing If We Were Villains, by M.L. Rio:

As one of seven young actors studying Shakespeare at an elite arts college, Oliver and his friends play the same roles onstage and off: hero, villain, tyrant, temptress, ingénue, extra. But when the casting changes, and the secondary characters usurp the stars, the plays spill dangerously over into life, and one of them is found dead. The rest face their greatest acting challenge yet:  convincing the police, and themselves, that they are blameless.

convincing the police, and themselves, that they are blameless.

“This is a rare and extraordinary novel: a vivid rendering of the closed world of a conservatory education, a tender and harrowing exploration of friendship, and a genuinely breathtaking literary thriller. I can’t recommend this book highly enough, and can’t wait to read what M. L. Rio writes next.” —Emily St. John Mandel, New York Times bestselling author of Station Eleven

Rules

- Since the book is being released on April 11, that’s when we’ll pick our winners. Five winners will be drawn at random from eligible entries received prior to midnight on April 10, 2017.

- To enter, leave a comment here on the blog (not on Facebook or Twitter) answering the following question: You’ve decided to quit your day job and become a full time villain. Which Shakespearean villain is your role model, and why?

- Entries must include an accurate, reachable email address, so we can contact you in case you win!

- Limit 1 entry per email address.

- Contest open to U.S. shipping addresses only.

- Publisher will handle shipping books to the winners.