OK, stop what you’re doing.

“Empty Space” is a love-letter to live theater, a nine-episode web comedy that explores and glorifies the world of diehard thespians, those hardcore beasts of the theater who soldier on against the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune because, after all, the show must go on.

That’s direct from their About page, and I don’t think I could describe it any better. Remember Slings & Arrows? Of course you do. The love of Shakespeare extends beyond the text. We love to be around other people who love Shakespeare. Put me in the audience, or let me watch from backstage or heck, let me hang out with these people in their normal lives. We all have a shared passion, and it’s great to be around. (And let me tell you, having hung out with theatre people back in college, “we all have a shared passion” has a whole double meaning I hadn’t even considered when I wrote it!)

We open with Kira, our Juliet, speaking directly to the audience while she sits in makeup. She’s open in her criticism of the crew, and we clearly see one of them flip her off in the background. “This is a mirror,” she says, “I can see you!”

Our story then parallels Mr. Shakespeare as we quickly see the two houses – “Montacrews” and “Castalets”, as the director dubs them – hate each other. The actors claim that crew are just has beens and wannabes. The crew claims that actors are, and I love this line, “Props with dialogue.” The feud escalates into a literal sword fight (albeit with prop swords) until the Prince/Director steps in to declare that the next time anybody starts something, they’re fired, banished from the theatre, you name it. Get the picture?

You can probably see where it’s going. We introduce Orson, a new Mercutio, after the old one falls off the stage and breaks himself. Orson then starts fraternizing with a pretty costume designer. How long before he’s off to the drug store for poison?

Ok, maybe it doesn’t go that far. I think that most of the parallels were just their way of showing that they could go there if they wanted to. This whole production – just ten episodes, running around ten minutes each – is wonderfully self aware, and I’m sure the theatre geeks who’ve actually gotten up there and done the half speed stage combat and the overly dramatized back stage romances will find even more inside jokes than I did. Heck I laughed out loud when they dropped in a random reference to a production being “post apocalyptic” like that explained everything.

The whole point is, as I quoted above, a love letter to live theatre. Everything but the kitchen sink is thrown at actors, director and crew. People are fired. Replacements do not live up to expectations. Props are switched. Russian mafia come looking for the stage combat guy. Yet the idea of the show not going on just never materializes. Everybody rolls with it. Because at curtain call, when the audience applauds? It’s all worth it. Always.

Oh, and if it sounds like I enjoyed the series? The epilogue (of course there’s an epilogue, haven’t you been paying attention?) knocked me out of my seat. Our Mercutio, who also happens to have written the show, comes out to address us. “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage,” he begins. “A man walks across this space whilst someone else is watching him and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.”

“Damn,” I think. “That’s really good. I mean, I get that, immediately. I understand that sentiment completely.”

“Peter Brook,” he continues.

“Oh, well, there you go,” I say to my empty living room.

He then continues his … what should we call it? A call to arms? A mission? About the actors’ duty to fill the empty spaces of the world with theatre at every opportunity. Seriously, it made me want to go enlist. I want to go find some guerilla Shakespeare now. Maybe I should start some…

…oh, and did I mention this is all entirely free online? Not on Netflix, not on Amazon Prime, not coming to a theatre near you. Just hanging out on a web page, every episode, just waiting for you to fill up some empty space in your day by binge watching it. So why are you still reading? Go!

Watch Empty Space

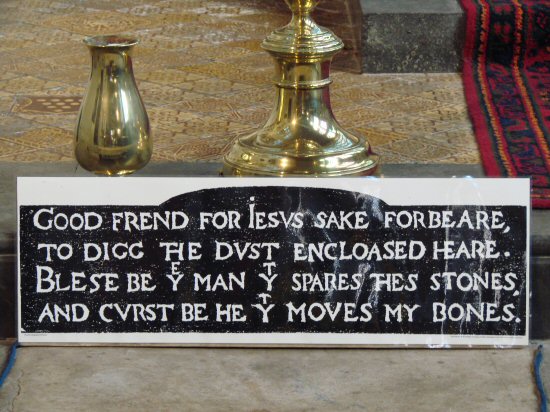

There’s been talk for years about excavating Shakespeare’s grave, and of course that’s never going to happen, but plan B has always been to scan the ground and see what’s under there because we just can’t leave well enough alone.

There’s been talk for years about excavating Shakespeare’s grave, and of course that’s never going to happen, but plan B has always been to scan the ground and see what’s under there because we just can’t leave well enough alone.