(This particular link made the rounds on Twitter already, but it’s definitely worth sharing far and wide.)

I’m not particularly enamored with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s new “Blogging Shakespeare” site which, five-plus years late to the party, seems to be positioning itself as the only Shakespeare blog in town. Since it’s a new project (just a month or two old) perhaps they’ll put up a Blogroll or some other link section and give a little acknowledgement to the now wide variety of other blogs that have been “embracing Shakespeare conversation in a digital age” for quite some time now. If their desire is truly to provoke conversation and foster community they might do well to start by engaging in some of the conversation already taking place in the already large community. I’ll be the first to admit that I need to link more blogs myself. I link a bunch, primarily for those authors who are regular contributors to the site, but I’m well aware that there are many I’m missing.

However, having said that I can’t help but be jealous that they’ve got Professor Stanley Wells blogging for them, and he writes gold like this about the new movie Anonymous, and the authorship question in general. We can all sit here behind our blog editors and take our pot shots from a distance, calling the anti-Stratfordians “loony” and getting all patronizing and eye-rolly … but Professor Wells is the guy who sits in the room with them and gets interrogated for hours on end. Literally. I don’t know that any of us could stand up to that for very long, at least without it breaking down into name calling and chairs flying.

Two specific points come out of this post that make me feel less anxious about the new movie. First, as Wells points out, this is not being positioned as a documentary, it’s going to be something more like Shakespeare in Love. I think very few of us had to explain to random movie-goers that Romeo and Juliet didn’t really go down like that. Second, and this from the comments, is that the actual theory being hyped – the one where Oxford is both Queen Elizabeth’s son and lover (ewww), might well end up looking so crazy that it works against the Oxfordians. So, that’s never a bad thing either.

Authorship is just one of those nagging conspiracies that I don’t think will ever go away. You’ll still find people who want to engage with you about who shot Kennedy, who was the mastermind behind 9/11, what Obama’s real birth certificate says … We as Shakespeare geeks can choose to ignore it, or we can dive into the conversation and try to give as good as we get in what will soon become a series of very personal attacks. It’s nice to take a moment, though, and remember that there are real people who do this for a living (although, as Wells says, they didn’t pay him for his interrogation while he sat on his “distinctly uncomfortable bench” 🙂 ). Their job is harder, and they deserve some credit and respect for leading the charge into battle.

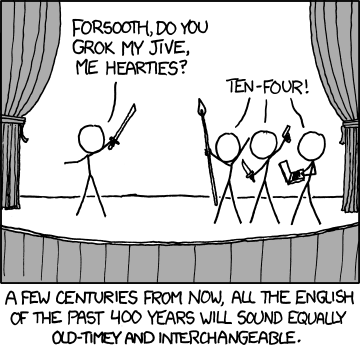

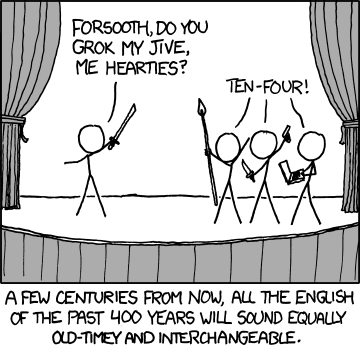

Geeks of the more technical persuasion will recognize, and probably already saw, this

Geeks of the more technical persuasion will recognize, and probably already saw, this