So Saturday was the big day! I’d been training my girls on Hamlet, so that they could actually understand what was going on before seeing the play produced by the local high school (where they’ll be going in a few years, and hopefully performing).

My son has religious education practice, so he couldn’t join us. Which gave my wife this opportunity to a quick cheap shot:

Son: How come the girls don’t have to go?

Wife: The girls are going to see Hamlet.

Son: How come they get to have fun!

Wife: They’re not. They’re going to see Hamlet.

Ouch. I’ll get you for that.

Anyway, the girls put on their Shakespeare is Universal shirts and we head to the show.

And, as always, I end up disappointed. In my brain I tell myself that I’m about to walk into a whole bunch of people of all ages who want to talk about Shakespeare, and education, and educating people about Shakespeare. I imagine people engaging my kids in conversation when they see their shirts. I imagine seeing parents whose kids got to read Hamlet last week because of me.

None of this happens. One volunteer says, “I like your shirt” to one of my girls, and that is the entirety of discussion. This is not a mingly crowd. This is a crowd made up entirely of parents whose kids are on stage. I don’t know what I expected (well, that’s not true, see above) but I should have known better.

While waiting for the show to start, my girls read the program and begin asking me who “Juggler” and “Lady Nora” are. I have no frickin idea who those people are, until we decide that they’ve given proper names to all of the Players. Fine.

My older then notices that the character of Hamlet shows up twice in the list. I figure that is understudy or something, but it’s not marked that way. We then realize that there are *5* Hamlets listed. All girls. Interesting. I assume that this is a case of the director needing to cast everybody who auditioned, or something.

The play begins, and out come … all the Hamlets? This should be interesting.

They immediately launch into the “too too solid flesh” speech, entirely out of context. They yell it, in sync with each other. I guess this is supposed to give us our backstory, because it touches on the death of Hamlet’s father and the o’erhasty marriage of his mother to his uncle. But honestly, what are you doing? If somebody came to this play actually trying to understand it for the very first time, why would you do that? Both my girls asked me what was going on, and I just shrugged and said I’d explain later. My expectations were all messed up now.

After the five Hamlets, then the play begins with the famous “Who’s there?” and the changing of the guard. At least from that point on, I’m pretty sure they stuck to the script.

The five Hamlets come out at the same time. Four hang back while one delivers lines. They often switch. During the big speeches they interchange their lines, speak in sync, and other gimmicky things. I’m still not sure what this is supposed to be. I thought maybe it could be some sort of “facets of Hamlet’s personality” thing, but I don’t think that’s what the director was going for – they are all dressed identically, even during costume changes. There is a certain progression of Hamlet’s insanity as his (her?) wardrobe unravels throughout the play, but that’s the only real development of this device I saw.

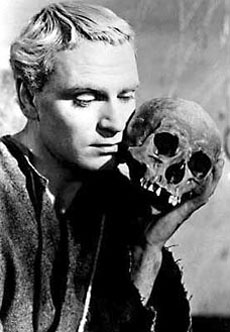

Followers on Twitter may have seen my rant about this, but THEY CUT YORICK. We have a gravedigger’s scene, including all the gravedigger jokes, and at one point the gravedigger starts pulling skulls out of the grave in front of Hamlet and Horatio. But, no Yorick speech.

I should mention that this performance is part of a “90 minute Shakespeare” festival. So there’s to be cuts. Sometimes, big ones. I do not envy the director who has to decide what to cut. But I am curious whether any of you cut the Yorick speech.

Other bits that were cut include Hamlet coming across Claudius at prayer and deciding not to kill him. Also, Ophelia only got a single crazy scene (before Laertes returns home). I think they just folded everything for her into the single scene, but I couldn’t tell you exactly what might have been cut.

What they didn’t cut? Fortinbras. All the Fortinbras scenes (including all the Cornelius and Voltimand scenes) remain. I thought that an odd choice, if they were aggressively cutting for running time. Take the ending, for example. Did we end on “The rest is silence”? Nope. Hamlet dies. Then Fortinbras (who the audience has only seen once) enters, and Horatio actually shouts his final lines, stomping up and down the stage, and I’m like, “WTF is he doing?” Fortinbras then gets the final lines, although I should go back and check my text because I did not hear “Bid the soldiers shoot.”

Observations from my kids:

* I pointed out when “To be or not to be” was coming. My oldest held out her hand and said, “No skull?” So she clearly was still getting the two speeches confused. I’ve seen lots of people do that. It doesn’t help that I have a t-shirt that shows the To Be speech drawn out in the shape of Yorick’s skull.

* My younger was mostly lost. It didn’t help that they could barely hear what was going on, so if they didn’t have a very clear understanding of the characters and plot to follow along, I could see where it would be confusing.

* They both spotted the doubling. The actor playing the ghost showed up in some other role, which they spotted…and I’m pretty sure that dead Polonius played the priest at Ophelia’s funeral, which was really confusing.

* During Ophelia’s singing, my oldest leaned over to me and said, “I am so doing this.” I asked, “You want to play Ophelia?” She said, “Well, any role, but Shakespeare definitely.”

* My oldest told me that she saw at least one fellow student from her class, and wondered whether he’d been convinced to come see the play after reading my book. I expect that the odds were more in favor of his sister being a Hamlet.

I only went to one performance of three, so I have no idea what the crowd was like at the other two. I’ve not yet received any actual feedback from the teachers who were using my text in their classes. I’d like to think that I helped, but honestly between the way they cut this production and the fact that it was impossible to follow the text when you couldn’t hear it, I don’t know how much I helped.