A copying error changes the meaning of Hamlet.

“What damned error, but some sober brow

Will bless it and approve it with a text…?”–The Merchant of Venice

Copying errors are pernicious. Once introduced, an error can be used as a template for a new copy, and that bad copy can be copied again, and yet again, until soon the error is everywhere.

I’ve identified many copying errors in different versions of Shakespeare’s plays. In one variant of The Taming of the Shrew, for example, L becomes T, and Bianca declares that she will “took” on her books and instruments rather than “look” on them.

Other equally nonsensical changes bring “jading” to a bay, rather than “lading,” and describe a girl as “cold and steM” rather than “cold and steRN.”

Once in while, though, an error will be introduced that actually makes sense. And these kinds of errors are really the most interesting ones. And the most dangerous.

The best example I’ve found comes from Hamlet.

Here’s the original, Act 4, Scene 3:

“A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and EAT of the fish that hath fed of that worm.”

At some point, though, the original E was swapped out for a C:

“A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and CAT of the fish that hath fed of that worm.”

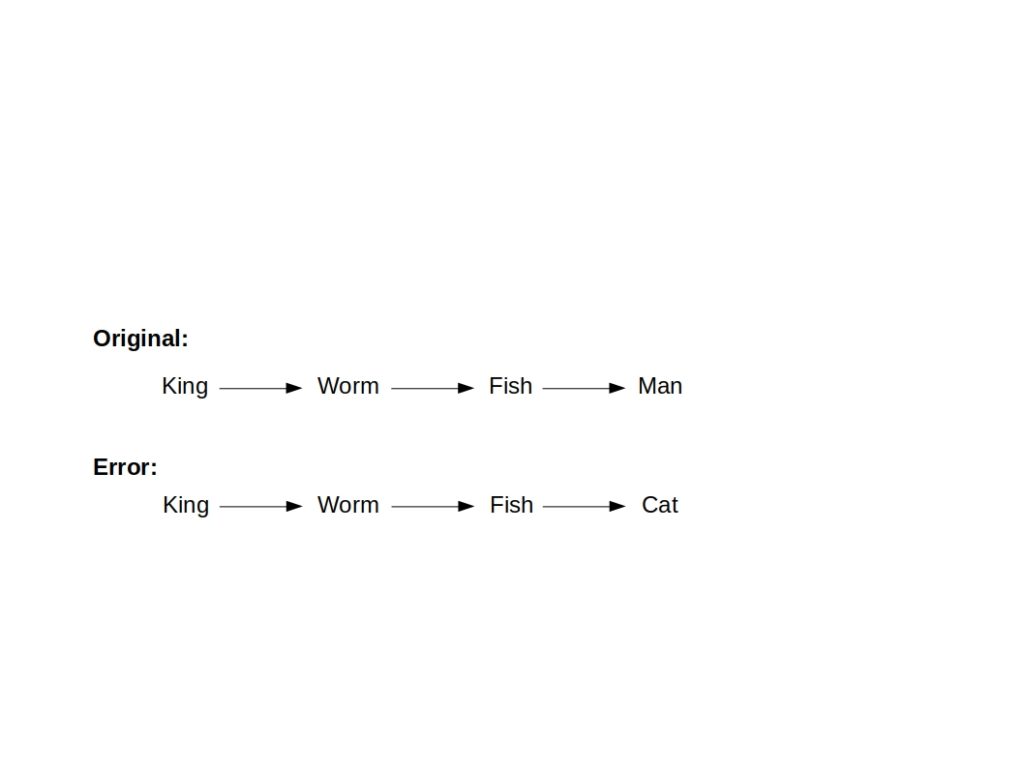

Both versions describe a food chain, one creature eating another:

In the first version, worm eats king, fish eats worm, and man eats fish. But, in the mutant version, the final recipient of the feast is a cat.

This second food chain, like the first, is 100% plausible. Cats DO like fish, after all. In fact, they are famous for eating them.

So: what could be more reasonable?

Reflecting this plausibility, this new version is now INCREDIBLY widespread. Reasonable people fixate on this section, and they quote it again and again and again and again.

There’s another weird twist to the problem. Because, to a certain kind of person–the cat lover–the mutant version may be even more attractive than the original.

For example, guess which version is featured in the book Planet Cat: A Cat-Alog under the heading “Shakespeare on Cats?”

It’s not the original.

It gets worse, though. Because the mutant version has spawned offspring of its own. In The Classics of Literature In Plain and Simple English (2012), the error is translated like this: “The same worm that eats a king may become food for a fish which serves as the dinner for a cat.”

Where did this cat come from? Perhaps Google Books is to blame. Certainly: it is now on the wrong side of the problem.

In a typical example, as here, the original text is from 1695, and is perfectly good, but Google Books suggests a transcription of “cat.”

This cat is an interloper. It should not exist. And so we are, of course, obligated to resist the error, wherever we find it.

And yet….There is a weird charm to this new version. And something very cat-like.

Shakespeare never intended this cat. But it crept it in anyway, unwanted.

And now that it is there, in everyone’s lap, rubbing its head persistently against our hands, sometimes, just sometimes–in spite of ourselves–we find ourselves petting it anyway.

Damn cat.

Rachel Rodman is a writer and a former scientist. She writes Shakespeare-inspired fiction and once designed an entire biology course framed using the complete plays of Shakespeare. She is currently working to promote creative ways to interweave evolution and popular culture. Her favorite evolutionary truism comes from The Tempest: “what’s past is prologue.”