So at long last I’m getting time – granted, 5-10 minutes at a shot, but still – to sit and enjoy my First Folio that I got for my birthday.

Wouldn’t you know it, I found something to post about in my very first sitting.

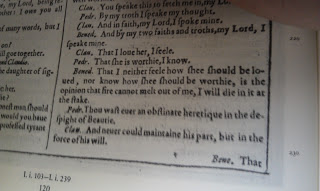

I’m reading Much Ado About Nothing and noticed that on the bottom right corner of every page is a single word (or two), which turns out to be the start of the next page. At first I thought this was a typo of some sort, and then noticed that it happens on every page.

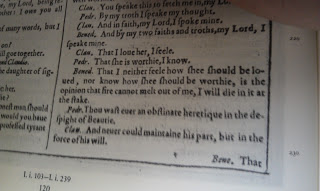

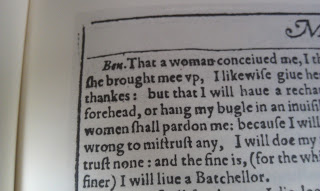

See that “Bene. That” at the bottom? Now check out the next page:

This happens all the time, whether it is one person who continues speaking, or the speaker changes. It does not always have the opening word like that – in fact, in a quick flip through I didn’t see any other examples where it included another word.

So my question is, what’s this all about? What purpose does that serve? Some sort of script clue to the reader about what’s about to happen on the next page, so there’s no unexpected break in continuity? That’s the only thing I can guess, although using just a single word to do it seems pretty minimal.

(By the way, it does not go unnoticed that the speaker abbreviations are all over the place. Sometimes he is ‘Bened’, sometimes ‘Bene’, sometimes ‘Ben’. The computer scientist in me hates that. Make a rule and stick to it, people!)

I assumed it was so that you would be able to anticipate what was going to be on the next page, but I guess I've never asked.

If that inconsistency irks you, the whole Folio is going to drive you bonkers! 😀 There are places where the same word is spelled differently twice in one speech (I assume to tip you off as to importance of the word, or pronunciation differences for scansion).

Hi Duane,

As Angela says, the whole

Folio is going to irk the

perfectionist in you…the

actors and director of Timon

at The Globe got to look at the

First Folio which was donated

to them, and the difference in

printing quality between it

and Ben Jonson's printed "Works" was very marked…of course,the

quality of the writing mostly

follows the opposite pattern!

I believe at least part of it is to assist in composition — to make sure the pages match up in the right order, to make sure the compositors start setting the next page with the right words, etc.

I find all of these inconsistencies really interesting — it's so much fun to me to think about these compositors, how they did things. (An ex-professor of mine has a really great theory about a drunken compositor, based on the patterns of his errors). Variant spellings really had nothing to do with keying scansion or pronunciation — spelling just plain wasn't standardised, and if the compositor was out of "e"s to use on that page, the spelling of a word could change. And punctuation! Bewildering and so interesting.

And then you'll get to the inconsistencies between plays in the Folio, since not all of them were set by the same compositor. Each one has his own quirks. Some like parentheses, some like dashes; some are very consistent with speech prefixes, some aren't at all. Some of them give act and scene breaks, others don't.

There's another fascinating textual oddity later on in Much Ado, that tells us so much about playmaking… but I think I'll let you find it on your own. 😉

What insights! I never really give thought to the the process after the story is written. Those are some very good points.

And it's not just Shakespeare's First Folio! I have a facsimile of the 1611 King James Version Bible, and it does the same thing.

I have a facsimile of a commentary of Galatians by William Perkins, and it has the same feature. So yes, must have been a normal practice in the print shops.

The words you have noticed are called "catchwords." They were invariably used in printing whenever more than one sheet was to be printed and then bound together. The purpose was presumably to allow the compositor to make sure he was putting his text in the correct place.

To understand why this practice was used, you to understand how typesetting was done. First of all, the compositor set the type in his "stick" upside-down and backwards. Each line was placed one after another in a "form." Exactly what was in each form (that is, how many pages that would appear in the book) would depend on the size of the book being printed, usually a folio or quarto.

What made things complicated, was that the compositor did not set the type for a book one page after another (in seriatum, as bibliographical geeks say), but rather "in forms." The form was designed so that when both sides of a page were printed, all the pages of a "quire" were printed (in the case of the First Folio, six full sheets), and then folded over (simple for a folio, a bit more complicated for a quarto) one could now flip through the pages from first through last and be reading the content in order.

It seems clear, though, that the compositors were clever enough that they did not need to rely on this system, since catchword errors appear every now and then throughout Shakespeare's works without having resulted in the compositor mixing up the pages.

Did you also note the little letters and numbers at the bottom of some of the pages?

The title page starts with "F." The back of the page (the "verso" to biblio geeks; the other side is call the "recto") never has a page indicator. The next recto page has "F2." You will also find F3, but the next 3 recto pages are blank. You have to wait for the next quire until you find a mark again, this time "G." By convention, the first page of a quire has just the letter, the next two are numbered sequentially (always starting with 2), and, for some reason, pages after the third are usually not numbered. No clue why.

Interested in bibliography? An excellent book: "An Introduction to Bibliography for Literary Students" by Ronald B. McKerrow (Oak Knoll Press, 1994).

I have a couple of articles in "Studies in Shakespeare" particular to Shakespeare, you could look up as well.

–Carl

While Carl hits the highlights of the publishing end, I'd like to address the notion that Shakespeare's spelling doesn't matter. It matters very much. He was writing his words the way he wanted his actors to say them. If he writes "war" it's a short sound. If he writes "warre" he wants to draw out the sound and emphasize the word. Same holds true for capitalization. This and the rules about punctuation and where to breathe has been codified as "Folio Technique." Shakespeare's company didn't have a director, there were very few rehearsals. The way to direct was through the writing. I remember teaching an actor about it as he was prepping to play Cassius in a CAESAR I was directing. He called me a few days later and said, "I'm totally weirded out. I feel like I'm being directed by Shakespeare."

Not that the Folio is the be-all and end-all – there are plenty of errors (Romeo dying twice, etc). But modern editors who "fix" the spelling and punctuation are removing a huge piece of an actor's craft.

Carl — I knew there had to be a word for that! Thanks for putting it in my mind. 🙂

David & JM — I'm all for anything that helps actors gain clarity over the words they're saying, but I think there are some problems with propagating Folio Technique as a scholastic theory rather than as a modern rehearsal practice. Shakespeare didn't really have control over the texts once they went to the print house. For one thing, the plays belonged to the company, not to him — Shakespeare likely had no control over *if* they went to print, much less over the details of them doing so. (And the actors wouldn't have been using the Folio text, obviously — since it came after he was dead; the Folio was set off of fair copies, prompt books, or quartos — all of which were already at least one or two degrees removed from Shakespeare's hand). We know printers changed things to suit the needs of their medium. We know printers made errors. Besides variants between quartos and the Folio, there are sometimes even variants inside an individual print run.

There's a really fun thing you can do, actually, if you can look at more than one copy from the same print run, because you'll find errors or variants in one copy that aren't in another, indicating that someone found the error and literally "stopped the presses" to fix it mid-run. There are some Hamlet texts that are really great for that, or the Richard III quarto text where "the souls of men are full of bread" instead of dread. And so it's impossible to say that any variant spelling was Shakespeare's intention rather than an effect from the compositor. There are too many other hands in the mix by the time we get to the texts that we see.

We go back to the Folio at the ASC because it's (generally) the closest we can come to what first flowed from Shakespeare's pen — but it isn't that itself. It can be a great tool for exploration — personally, I love taking out the modern scurrilous exclamation points that editors seem to think the text needs — and it's a really intriguing way to help an actor discover new ways to play the words, but I just don't think there's a sound scholarly claim for Shakespeare directing through spelling.

If anyone interested in bibliography can make it to Staunton this summer, William Proctor Williams is going to be here giving a fantastic lecture on all things bibliographical at our No Kidding Shakespeare Camp. He'll explain (much better than I can) all the nuances of textual transmission and the many, many hands the plays as we know them passed through. I'd also recommend Tiffany Stern's book Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan for more information on how Shakespeare could have conveyed information to his actors embedded in the text.

JM – I'm right there with you. There's a reason they didn't say, "Let's go see a play" in Elizabethan times. They said, "Let's go hear a play." It's all about sound.

JM — And like I said, if it's helping you in practice, that's brilliant and I'm glad. It's just that *anywhere* we start talking about "Shakespeare's intentions", the waters are pretty muddy, because there's so much we don't and can't know — we're all just making the best guesses we can. I'm not a bibliographical scholar myself, but I've had the great fortune to learn from a lot of the very best of them — and from everything they've taught me about printing practices, I just find it impossible to place that much trust in something that was completely in the printer's hands, not Shakespeare's. And sometimes that makes it frustrating for me as well! I edit off of the Folio for our Study Guides, and sometimes it's really apparent that the printers have made an error (wrong speech prefix, breaking meter, rendering verse as prose or vise versa) — so what do I do? Leave it the way the Folio has it, or shift it to what seems more natural? Balancing what I know about textual transmission with what I believe about how Shakespeare wrote can be a challenge, and I always have to guard about making inaccurate assumptions or projecting too much.

I have a question, then — Do you ever look at the other texts for those which are present in Quartos before the Folio? How would you synthesize that into your process — particularly if you find something like the same line printed as "here" in Q1, "heere" in Q2, and "heare" in F? Is that just permission to try it different ways and see what works?

David,

Let me reiterate. "A man after my own heart."

I'm also a proponent of the Folio Technique; learned about it years ago in NY at Riverside shortly after Tucker and Barton and company brought it across the pond. Sadly, Riverside Shakespeare Co. is no longer. But they're credited with being among the first at introducing the importance of Folio analysis in Shakespeare performance here. Without it, I'm not sure I would have ever gotten a handle on the dreaded Bard we actors can have so much trouble with.

It also helps in explaining how SOUND was the major tool, not some Freudian inward analysis of emotion. DO the Wordies and they wind up doing you. The rest will follow.

I use the technique in teaching, directing, acting, analysis–in fact, in everything I do when it comes to Shakespeare. Combine it with punctuation cues and the so-called "literary" analysis and you've got a key that opens doors which never would have appeared at first glance. As you say, you don't have to push yourself through those doors, but at least you know they're there. Sometimes even the antithesis of a discovered choice can reveal itself as a solution.

–eg., I've noticed that even what might sometimes be assessed as 'compositor' decisions or 'errors' can sometimes spark thought.

The Technique was an amazing and fortuitous discovery I'm grateful for every time I open The Book.

JM – Couldn't have said it better. I was making much the same point to our gracious host on FB, but was hesitant to wade in here, fearing to be inartful. I'd like to amplify one of your points – if we accept the word choices in the Folio, and decide those are (for the most part) not in error, why disregard the spelling of them? Picking and choosing which part of the Folio is "right" is as contradictory as it is self-defeating.

Cass, to your Quarto question – as an actor and director, I use it all. Folio Technique is a great tool to have in the kit, and a fantastic starting point. But it's not Holy Writ. I've used the "Benvolio is deceased" line from the first Quarto in some productions, dropped it from others. I've seen companies that memorized both the Quarto and the Folio Hamlet, and performed them on alternate nights. I imagine JM does much the same as we do, taking the pieces that best fit the show we're producing. It's all grist for the mill. It's just the the Folio is a fantastic grounding, a solid floor under our feet to begin work.

I'm not advocating rigid adherence to it. I just object to it being dismissed in the name of "scholarship." Everything about Shakespeare's life and writing is inferred, not explicit – that's why there's an authorship controversy. So if everything is inferred, why object to this? It works far too well, and makes far too much sense, to cast it off out of hand.

Cass,

As you know, Elizabethans spelled words as they heard and spoke them. There were no spelling "rules" and no dictionaries. Foul Papers, Fair Copy, Prompt book, Heminge and Condell, Compositor, Printer–all givens and accepted as possible controlling variables–many dramatic/performance threads, vis a vis our topic–running through the

Folio are, in my opinion, repetitive upon close analysis. After all, the main controlling variable we might assume is the Source– Shakespeare– an actor himself. Might we also assume the possibility that that he *heard* his actors speaking *as* he wrote their lines?

However right or wrong I might be about that, I make no claim to an actual attempt at any scholarly thesis of any kind; but to ignore the possibility out of hand because of a printer's whimsy, while accepting, in its entirety, the rest of the "scholarly" analysis of the "literary" genius (or lack of same, as some of them have claimed through *their* changes ) as it found its way onto the page? It

seems a little short-sighted to me, as well as a little conflicting in the basic construct of its own theoretics. Compositors only messed with spelling and capitalization, ergo, everything else we've come to accept in scholarly analysis is valid *but* that? What's left? Versification, punctuation–things the scholars also think they're right-on about, but that change again and again over centuries according to *their* whimsy? I've found many instances of their changes in that regard, claiming intent from Shakespeare, which only serve to destructively muddle the rhythm and tempo of the verse and scene itself.

Sure there are a lot of obvious mistakes. But I find it hard to reason away possible intent when it shows itself.

I've employed the cues, over and over, and witnessed their great utility. You're right. It's not Scholarly 'Holy Writ'. The only thing I'm really sure of is–it just seems to work somehow. Maybe it's simply constructive rationalization on my part–maybe not. And if I infer in my teaching, "*Shakespeare* wrote: 'Heere', instead of 'Here' like he did later in the scene ", and it works for the actor to help in conveying a certain sense while speaking his lines in the scene, and the actor goes on to discover similar possibilities and is spurred on to greater creativity based upon this "formula"? Well, the scholars can shoot me. 🙂

Cass–Sure I consult whatever is extant. In compiling a performance version of Hamlet, I even poured over Q1 if you can believe it.

In the case of your examples, obviously the difference between "heare" and "heere" and which is a mistake is easily decided upon within the context of the grammatical construction of the sentence, one having to do with ears, the other with place.

For that matter, context is everything. "Synthesis", as you have rightly assumed, has to do with what *works*. If the instance makes no sense or has no function, then it's one of those "mistakes" or altered "variants" or simply inapplicable. But it has at least been noted for "something" and hasn't been ignored. As far as textual veracity, it can be a combination of selecting from all sources, as has been common practice with any 'scholarly' endeavor. (Hamlet Q2 and F1 a particularly obvious example.)

The detective work isn't always fruitful in a constructive way. But to ignore possibilities is against my nature.

As I said, I make no claims–nor did my teachers–as to complete veracity on any or all points. As you've said, danger lies therein.

But that has little or nothing to do with the point of the exercise. The point is *discovery*–right, wrong, or indifferent. What makes it *right* lies only in the success of its own utility, not in making out and out pronouncements or dictums as to Shakespeare's true intent.

To entertain the *possibility* of intent and the search for same is key here. That's what can inspire.

Speaking of grammatical oversights I didn't "Pour" over anything, I pored over it–Jeez.

David,

I've always found the Folio Technique difficult to "explain", so to speak. It's hard to accept a set of "rules" that do exist but aren't set in stone, if I'm not being too cryptic? Before they truly get it, even students sometimes want to set hard and fast rules and tie me down to absolutes–I guess in an effort to feel secure. But eventually, in action, it explains itself.

the ans is that the folios are meant for actors not for readers. shakespeare wrote for hearing and acting not for reading. it ws to alert current actor that who speaks next. or for next speaker to know.