(London, 2 May 1592)

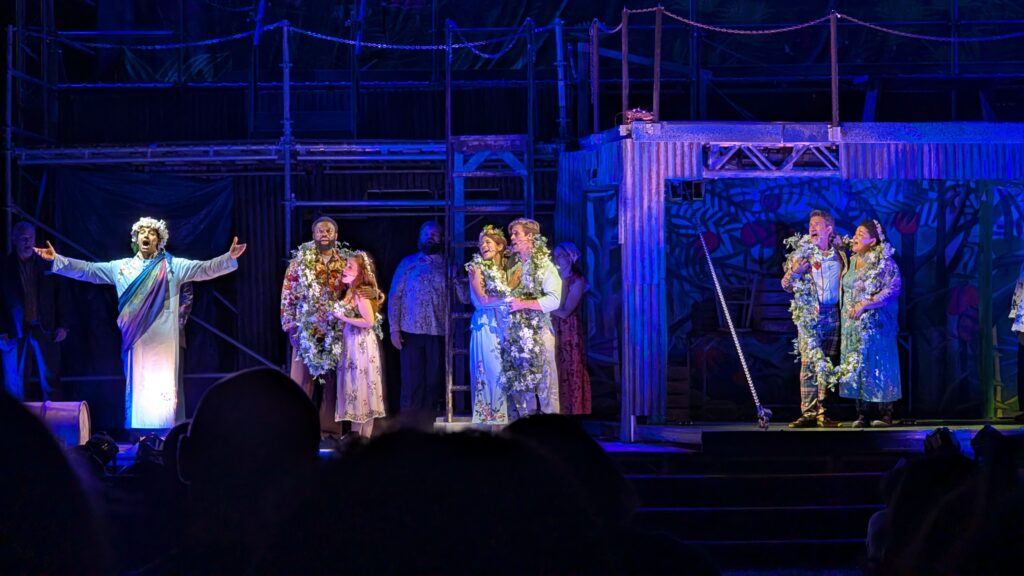

The roar that greeted Will as he stepped into the Curtain was not for him. It spilled from the bear-pit beyond the north wall—thirty dozen voices baying for blood, human and animal at once. He paused, manuscript satchel clutched to his ribs, and wondered how many of those throats would ever bother cheering a play.

Inside the play-yard, the atmosphere felt brittle. Rehearsals were meant to be private, but plague gossip had drawn a knot of groundlings who could not afford to wait for opening day. They leaned against the stage like sailors against a rail, hungry for any scrap of performance. Will felt their eyes rake across him—country cut of cloak, ink under fingernails, the faint smell of river fog still clinging to his boots. He straightened, trying to look as though he belonged.

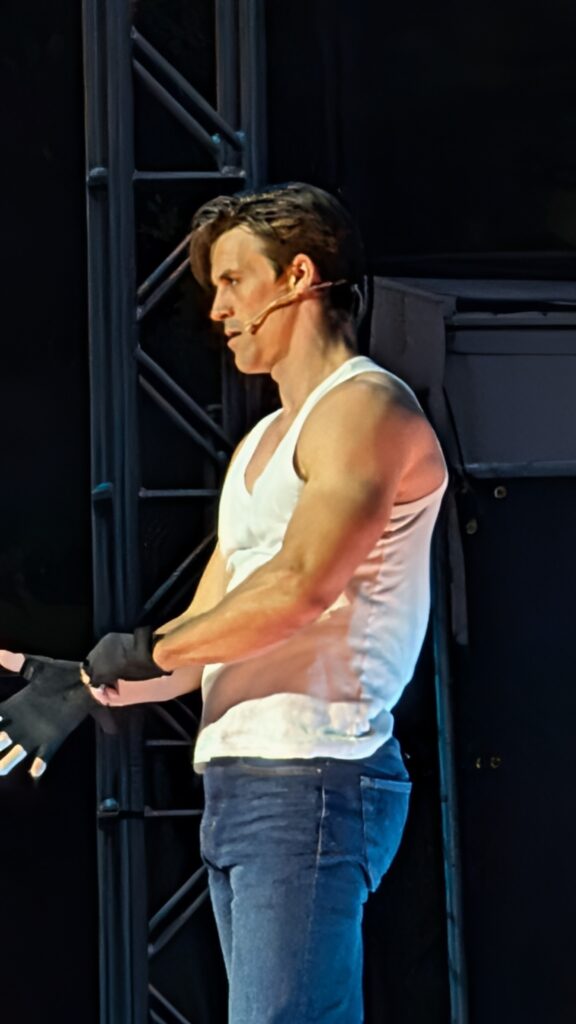

Ned Alleyn stood centre-stage, one fist on his hip, the other brandishing a paper crown that drooped whenever he moved too quickly. “No, Master Shakespeare,” he called, not bothering to turn, “Tyrants do not whine. They declare.” He flung the line outward like a gauntlet:

“‘Now is the winter of our discontent…”

He stopped, grimaced, and let the crown slide off entirely. “And what manner of winter is this? A mild spring drizzle?”

Will felt heat crawl up his collar. He had laboured over that opening for weeks, trimming and tuning until each syllable sat like a bead on wire. He climbed the side stair, boots thudding against the hollow boards. “The winter is metaphor,” he said, keeping his voice low enough that only the stage heard. “A frost within the soul, not without.”

Alleyn raised one famous eyebrow. “Then give the soul a coat, sir. I freeze.”

A ripple of laughter travelled through the small crowd. Will swallowed it like vinegar. He was unbuttoning the satchel, ready to thrust pages at Alleyn, when a familiar laugh floated from the yard.

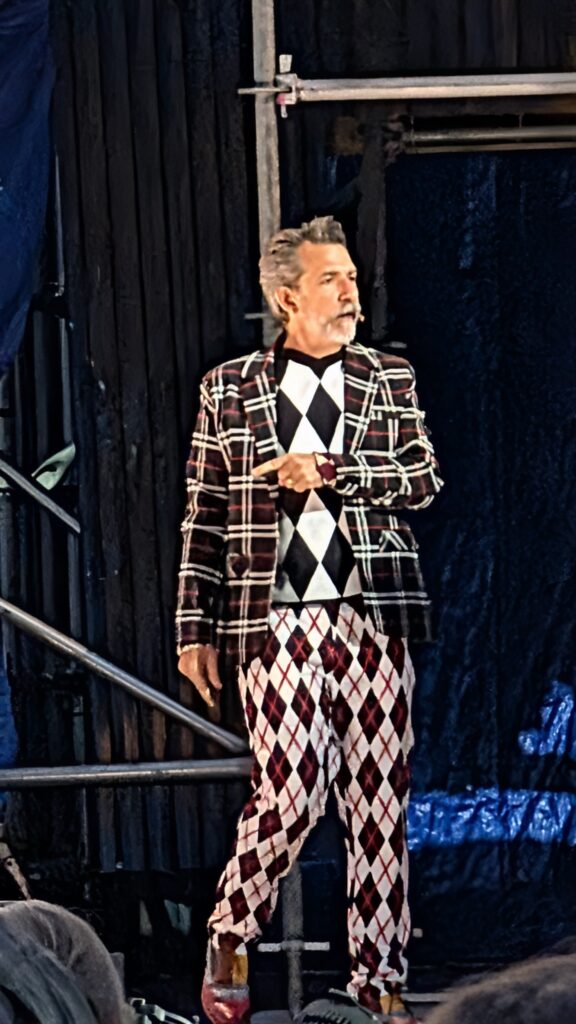

Kit Marlowe leaned against a pillar, moonlight catching the silver hoop in his ear. He looked as though he had been there for hours, drinking in every stumble. He lifted two fingers in lazy salute. “Trade you a line for a line, countryman,” he called. “‘Grim-visaged war hath smoothed his wrinkled front,’ and left it to you to wrinkle it again.”

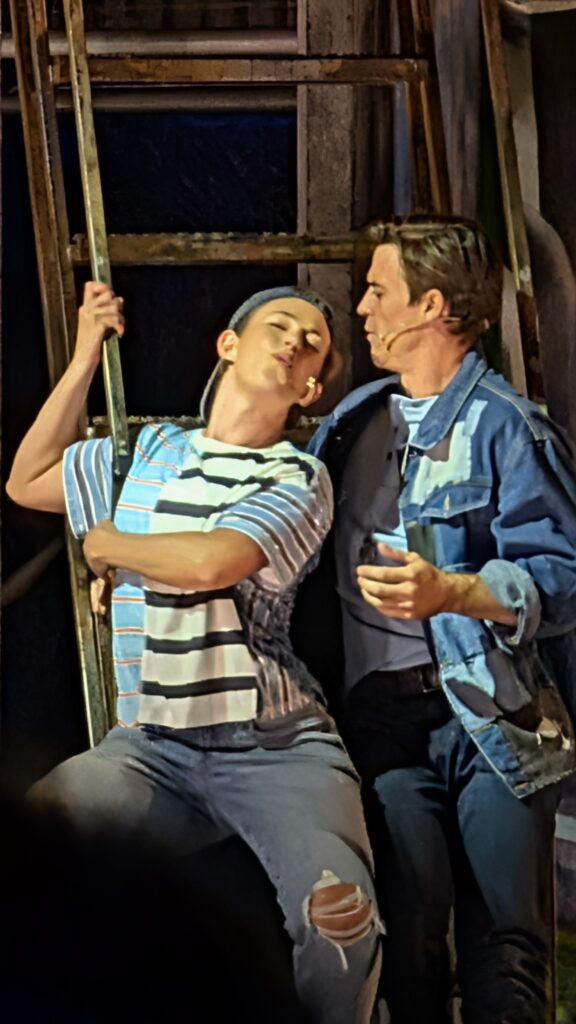

Will’s pulse stuttered between irritation and relief. Part of him wanted to drag the man backstage and demand why he had vanished after the Bear Garden; another part felt the sudden, shameful comfort of a friendly blade in hostile territory. He descended the stair, meeting Kit at the foot of the stage.

“Deptford tomorrow?” Will murmured.

“Tonight, if you’ve the stomach,” Kit replied. “But first we mend this speech. Trust me, Ned will mouth whatever we give him, provided it sounds expensive.”

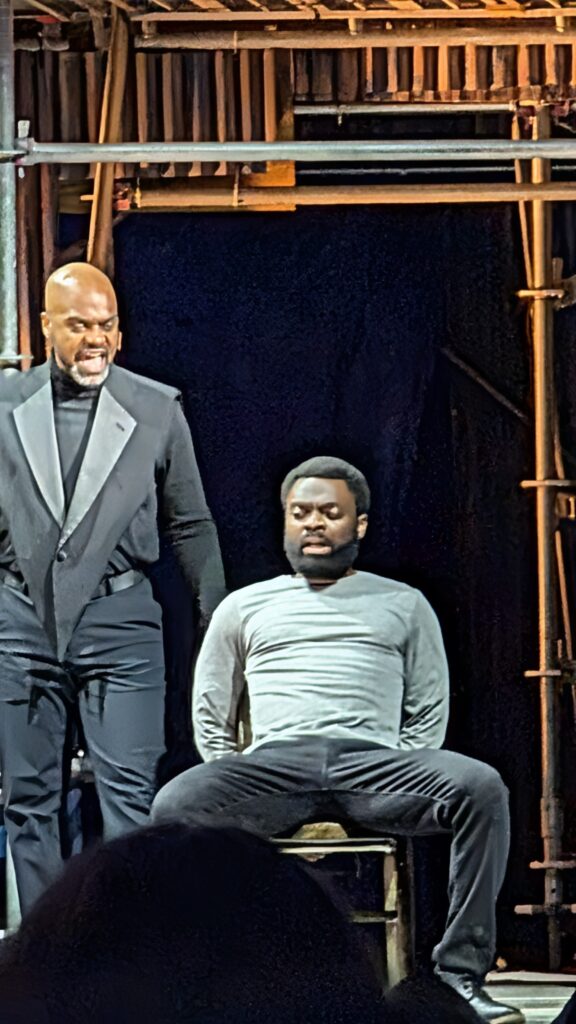

Before Will could answer, a trumpet sounded. Not the bright flourish that called playgoers to merriment, but the flat, official note used by town criers. The yard fell silent. A bailiff in city livery stepped through the playhouse gate, scroll in hand, voice cracking like winter ice:

“By order of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen, all common plays and interludes are to cease forthwith, the plague having increased these four weeks past. Houses to be shut, gatherings dispersed. God preserve the city.”

He nailed the parchment to the door and was gone, boots splashing mud across the threshold.

A collective exhale, half groan, half gasp, swept the yard. Alleyn let the paper crown fall to the boards and trod on it without noticing. Somewhere a woman began to weep; somewhere else a groundling cursed and spat. Will felt the news hit him like cold water: no performance meant no gate money, no gate money meant no rent, no rent meant the long road home to Stratford with nothing in his purse but cherry-blossom promises.

Kit’s hand found his sleeve. “Breathe, countryman. There are other stages.”

“Where?” Will’s voice came out rough.

“Private halls. Noblemen’s chambers. Even,” Kit lowered his voice, “the coast, if you can stomach a ship.” He steered Will toward the tiring-house door, away from the rising tide of panic. “First we save your play from Ned’s boots. Then we save ourselves from the plague. And then,” his smile flashed, reckless, “we make our own audience.”

Behind them, the parchment flapped against the oak like a dying bird. The Curtain had fallen silent, but in Will’s ears the roar of the bear-pit still raged. Only now, he wondered if he and Kit were the bears, and London the crowd that would soon demand blood.

Next Time: A locked playhouse, a borrowed candle, and two poets rehearsing Richard III to an audience of rats. Chapter 5: “By Candle & By Quill.”

The playhouses are shuttered, the bear-pit still roars – would you risk the plague for one more line on stage, or take the first ship out of London?