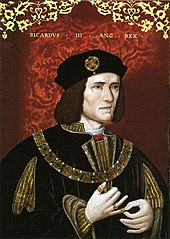

What really happened to the two princes in the Tower? It’s one of history’s most haunting mysteries—two royal brothers vanish, a crown is taken, and centuries of speculation follow. Now, the researcher who found Richard III’s bones under a car park is back, and she thinks she has the answer.

Richard III has a fairly high body count, however you count it.

He’s directly responsible for at least ten deaths—give or take, depending on how you tally things like Henry VI, whose murder happens in the previous play. But we all know Shakespeare wasn’t aiming for strict historical accuracy. He was writing to entertain and to please a Tudor monarch. Truth got a few edits along the way.

One of the coldest acts—on stage and in history—is the disappearance of the two princes: Edward V and Richard, Duke of York. In the play, Richard has them smothered in the Tower. In real life? They just… vanished.

Or did they? 🎵 dun dun DUNNNNNN!

What Happened to the Two Princes in the Tower?

Enter Philippa Langley—yes, the same researcher who found Richard III’s remains under a car park in 2012. She’s been on this case for years, and she’s not just speculating; she’s been digging (literally and figuratively) through archives, and she thinks she’s found something significant.

You may have heard of Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck, two men who claimed to be the missing princes after the death of Richard III. Both were dismissed as imposters. Case closed, right?

She and her research team have uncovered documents suggesting those boys may have been exactly who they claimed to be. One example? Receipts from 1487 supporting a rebellion by “Edward IV’s son”—the same year Simnel led his uprising and was crowned in Dublin. Langley has uncovered new references to the boy being “called” or believed to be “a son of King Edward.” She thinks that points to Simnel being Edward V himself.

So, what do the historians think? Langley has earned credibility with the discovery of Richard’s remains. This isn’t just a publicity stunt—it’s the continuation of a long, serious investigation. And it definitely has me curious.

Of course, even with new evidence, the question of what happened to the two princes is thorny. Traditional accounts lean heavily on Richard III’s guilt, but most of those sources were written under the Tudors—who had every reason to paint Richard as a villain. Thomas More’s account, for instance, is vivid and damning, but it was written decades later, under Henry VIII.

That’s why Langley’s work is so interesting. She’s not just rehashing old chronicles; she’s digging into primary sources that have been overlooked or misfiled, tracing networks of payments, correspondence, and political maneuverings that hint at something far more complex. What if Edward V didn’t die in the Tower at all? What if his identity was suppressed and replaced with the “pretender” label for the sake of stability?

Langley’s argument, if it holds up, would radically shift our understanding of that period. It suggests that the official story—the one we’ve accepted for centuries—might have been more propaganda than truth. It wouldn’t be the first time history was written by the winners, especially in a shaky new dynasty like the Tudors.

Naturally, not everyone is convinced. Many historians remain skeptical, arguing that the lack of hard evidence (especially forensic) keeps this in the realm of interesting theory. But Langley’s success with the Richard III dig gives her a level of credibility that’s hard to ignore.

Whether you buy the theory or not, it’s a fascinating reminder of how much we still don’t know about the past—and how much can still come to light, even centuries later.

What do you think?

Who’s excited for the return of Shakespeare Uncovered?

Who’s excited for the return of Shakespeare Uncovered?

So I saw this Entertainment Weekly article about 2o Classic Opening Lines in Books. For the curious, it stretches 20 pages for 20 lines, includes Harry Potter and does not include Orwell, Camus or Kafka. Of course there’s no Shakespeare, since it’s always up in the air whether someone counts his work among “books”.

So I saw this Entertainment Weekly article about 2o Classic Opening Lines in Books. For the curious, it stretches 20 pages for 20 lines, includes Harry Potter and does not include Orwell, Camus or Kafka. Of course there’s no Shakespeare, since it’s always up in the air whether someone counts his work among “books”.