EDIT: I just realized that the beer post isn’t scheduled to go out until tomorrow. Was everybody confused? 🙂

And I’m ok with it.

I’ve written about how last week not one but two separate coworkers sought me out to tell me about a Shakespeare-branded beer (“ShakesBeer“). We’re still on the hunt for that one.

This morning a different coworker tells me, “I got this chocolate bar at the supermarket that had some sort of Shakespeare quote on it. I took a picture of it for you, but it’s on my wife’s phone.”

I’m intrigued. I knew about the beer, but the chocolate was new to me. I googled around, found some random novelty items, and told him, “Sounds like one of those independent brands you find at Whole Foods. Never heard of it. But definitely tell me more!”

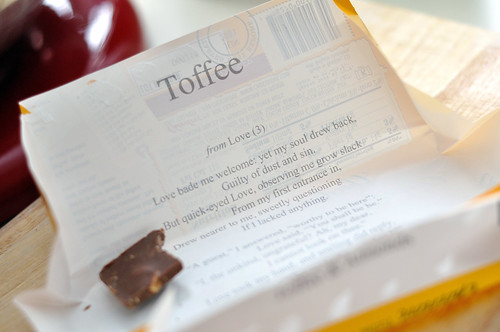

While waiting for his wife to get back to him I decide to throw the question out to the Twitterverse, noting that “some sort of Shakespeare quote on it” actually meant “a sonnet inside the wrapper” which is even cooler.

Twitter delivered. Both @magpiewhale and @katep08 said that he’s surely talking about Chocolove, adding that “this brand is delicious.”

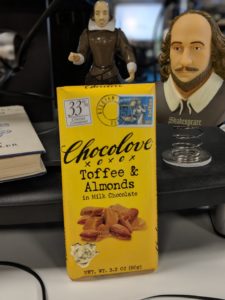

“That’s it!” says my boss. Then he sends me this picture that he’s googled, since we have a name now:

I’m crushed. “That’s not Shakespeare,” I tell him after reading about four words.

“I guess each one has a different poem,” he tells me.

Well, now the hunt is on. Their website has a “find a location” section and sure enough, it’s exactly what I suspected originally – straight to Whole Foods for me!

Success!

They actually have at least half a dozen flavors, but most of them were dark chocolate and I’m not as much of a fan. But I’m probably going to make multiple trips, who am I kidding. I swear I felt like the kid in Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, peeling open the wrapper slowly to unveil the golden ticket inside.

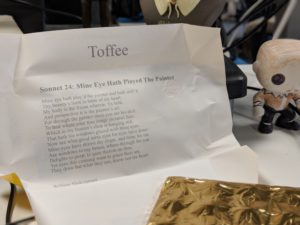

But did I get a Shakespeare or not?! The suspense! I did! Sonnet 24, to be precise.

I did! Sonnet 24, to be precise.

A joyous day to be sure. The chocolate is pretty good, but I felt twelve kinds of guilty eating it, so noting that I was only in it for the Shakespeare, I put the rest out for my coworkers. One of whom, also a Shakespeare fan, examined the outer wrapper and announced, “It doesn’t say Shakespeare anywhere on the outside. What do they think, I’m going to spend good money for Keats?!” 🙂

And yes, I have a shrine of Shakespeare action figures and bobble heads on my desk at work. Doesn’t everybody?

P.S. – Last week beer, this week chocolate. I can’t tell if the universe loves me or is trying to kill me. Either way I’m ok with it, I’m going down happy.

P.P.S – Also! These are apparently part of the Whole Foods / Amazon Prime program, if that’s available in your area. So if you’ve done whatever soul selling thing you do to let Whole Foods know you’re a Prime member, you can get them at a significant discount. In my neck of the woods it was $3.19 for a single bar but would have been $4.00 for 2 bars if I had my accounts linked.

So here’s a thought that occurred to me the other night. Bear with me, this is a strange one. But what the heck, it’s my site, the whole point is supposed to be my ideas about stuff.

So here’s a thought that occurred to me the other night. Bear with me, this is a strange one. But what the heck, it’s my site, the whole point is supposed to be my ideas about stuff.