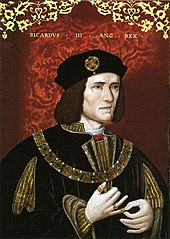

Romeo + Juliet (the one with Leonardo DiCaprio) is playing in the background as I work in the home office. Can somebody tell me about Mercutio’s final moments, specifically the reference to worm’s meat?

He is a friend to the Montagues and defends Romeo’s honor in his last act. Yet his last words are, among other things, “They have made worm’s meat of me” and the more recognizable, “A plague on both your houses.”

Help me into some house, Benvolio,

Romeo and Juliet III.i.106

Or I shall faint. A plague o’ both your houses!

They have made worms’ meat of me: I have it,

And soundly too: your houses!

Yes, But What Does Worm’s Meat Actually Mean?

If people find this post looking for an actual explanation of that worm’s meat line, it’s an image that Shakespeare uses frequently. You die, you go in the ground, worms eat you. Look at how Hamlet describes what’s happening to a now-dead Polonius:

Not where he eats, but where he is eaten: a certain

Hamlet IV.iii.22

convocation of politic worms are e’en at him.

Or Sonnet 76:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Sonnet 76

Then you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world, with vilest worms to dwell:

Pardon the pun, but Shakespeare and the people of the time were down to earth when it came to death. Death was a sad reality; people were dying all over the place. There could be plenty of taken of heaven and angels, to be sure. But when it came to what happens to your earthly remains? Shakespeare was very frank and often pretty gross about it.

Now, Back To Our Story

In this particular version, Mercutio wanders offstage alone when he utters the worm’s meat line as if it is an aside. That changes it for me. I always thought he was saying it to Romeo, referring to the Capulets. But said like that, coupled with the “both houses” line, it seems more that he’s talking about both of them. In his final moments, it is as if he’s wondering, “Why did I get in the middle of that?”

I suppose it’s always been there, and he clearly says both your houses. I don’t think it fully sunk in for me before. He doesn’t blame Tybalt for killing him. He blames them both for getting him stuck in the middle. My point is that the worm’s meat line is more important than the “both houses” line. Imagine for a moment that Mercutio’s not dying. He’s just angry that he’s been wounded for a dumb reason. The “both houses” line can still be hurled at Tybalt and Romeo, but it has more of a “You can both go to hell” edge. But the worm’s meat realization – especially said to himself, where “they” is clearly “both of them”, changes it. Mercutio knows he’s dead. The man with something to say is left with nothing but a curse to deliver.

So I saw this Entertainment Weekly article about 2o Classic Opening Lines in Books. For the curious, it stretches 20 pages for 20 lines, includes Harry Potter and does not include Orwell, Camus or Kafka. Of course there’s no Shakespeare, since it’s always up in the air whether someone counts his work among “books”.

So I saw this Entertainment Weekly article about 2o Classic Opening Lines in Books. For the curious, it stretches 20 pages for 20 lines, includes Harry Potter and does not include Orwell, Camus or Kafka. Of course there’s no Shakespeare, since it’s always up in the air whether someone counts his work among “books”.